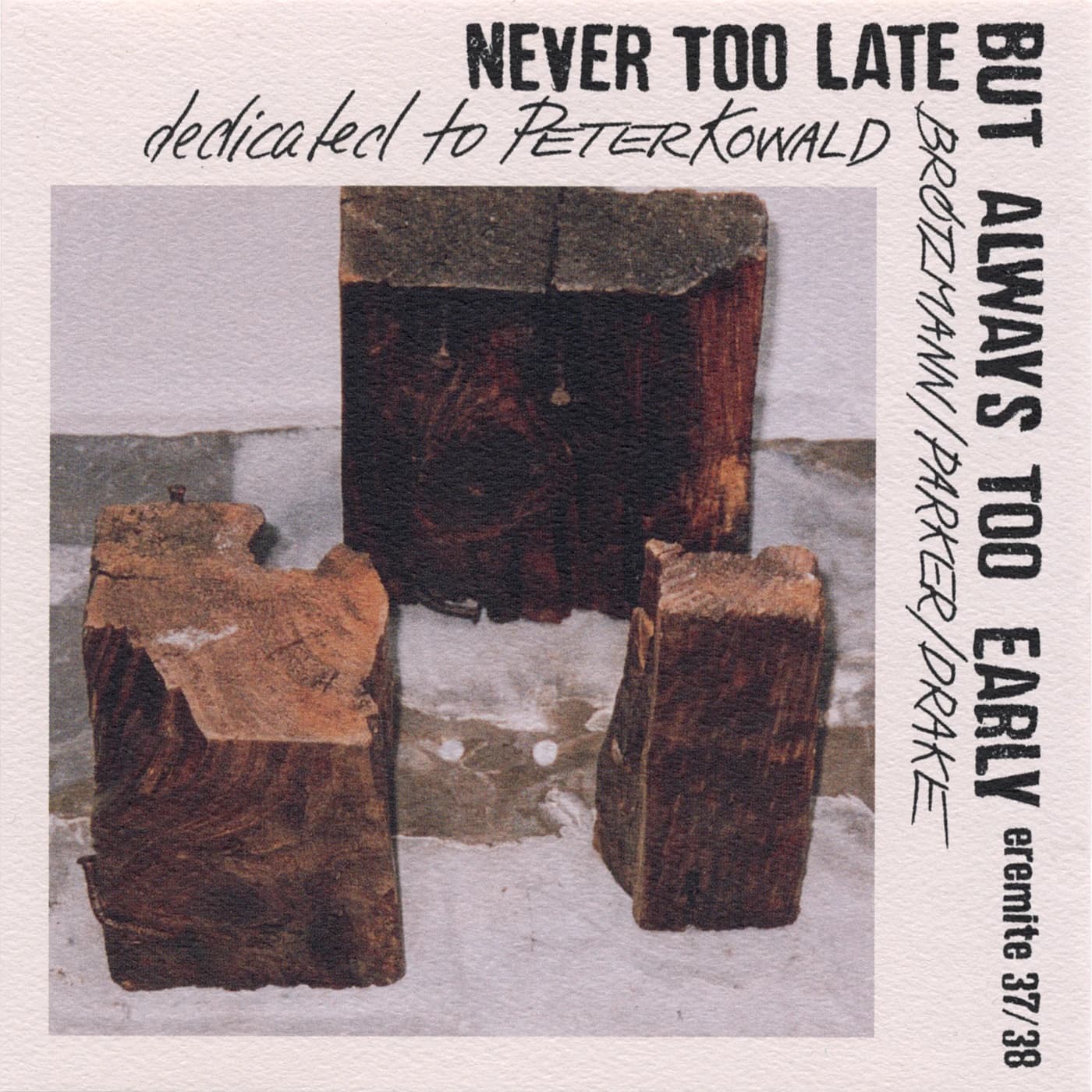

Never Too Late But Always Too Early (Dedicated to Peter Kowald)

Peter Brötzmann/Hamid Drake/William Parker

Out of Print

Personnel

Brötzmann tenor sax, tarogato, a-clarinet

Drake drums

Parker bass, doussin gouni

Track Listing

MTE-37

- Never Run But Go I (19:19)

- Never Run But Go II (04:47)

- Never Run But Go III (09:31)

- Never Run But Go IV (09:51)

- The Heart & The Bones (18:26)

MTE-38

- Never Too Late But Always Too Early I (16:51)

- Never Too Late But Always Too Early II (11:02)

- Never Too Late But Always Too Early III (17:52)

- Half-Hearted Beast (07:41)

Audio Clips

Never Run But Go III

13.09 MB

Recording Notes

2001-04-10, Casa Del Popolo, Montreal, QC

producer Michael Ehlers

engineer The Eremite Mobile Unit

design Brötzmann

liner notes Brötzmann

Description

founded in 1993, peter brötzmann's die like a dog band is widely regarded as "one of the leading ventures in the history of avant-garde jazz" (all music guide). its fusion of brötzmann's explosive "kaput music" with the omni-sourced rhythms of hamid drake & william parker makes for one of the most exhilarating ensemble sounds in music. a two c/d set, never too late... is the trio's complete concert from 10 april, 2001, montreal. eremite recorded every north american performance by the group from 2000 to 2005, & never too late (dear friends) is the motherfucker of them all. cover art & liner notes --an intimate remembrance of his late friend peter kowald-- by brötzmann.

the wire magazine #1 'jazz record,' 2003 rewind

cadence magazine readers poll, #1 record 2003

cadence magazine editor's choices, 2003

coda magazine writer's choices top ten recordings 2003

chosen as one of the "crucial" brötzmann recordings in the wire XI 2013 brötzmann primer

Press

Homages to the late Peter Kowald grow more numerous, but few will match the searing, visceral pull of this two cd set etched by some of his closest friends & associates in Montreal's Casa Del Popolo in 2001 & dedicated to Kowald after his death in 2002. Peter Brötzmann is a specter of grim emotion & raw energy, whether he's playing tarogato, tenor, or a clarinet in A. He is one of the great existential improvisers of free jazz, in that his intensity does not seem to move toward transcendence but instead speaks of expanding passion. It is because of Brötzmann's emotional register that this epitaph in advance to Kowald is so fitting. Pain, loss, distance seem so central to the saxophonist's expression --witness the tenor dirge of part 4 of "Never Run, But Go" which seems to refer directly to 'taps'-- that the specific subject only awaits naming. William Parker & Hamid Drake support, structure & alleviate Brötzmann's testimony, adding & sustaining pulsing patterns that invoke African & Afro-Cuban ceremony. On the first segment of the title piece Brötzmann launches a bass clarinet solo in which human cries are seemingly muffled in the instrument's woolly depths until they break out into screams in the middle register. Parker & Drake seem to ground & share in this witnessing, until Parker begins an extended & especially powerful bowed solo.

Eremite producer Michael Ehlers captures one of free jazz's finest trios live in concert in Montreal on this stunning double c/d recording, Which is --considering the prodigious output of the players-- incredibly one of the group's best on disc. Peter Brötzmann, William Parker, & Hamid Drake have been playing together for years now, & there is an instinctive synergy among them that is clearly evident on every track. As with many of Brötzmann's later performances there is plenty of slash'n'burn intensity but there are also many moments when Brötzmann turns inward to focus on colors, shading & nuance. There are numerous highlights, from the usual thrilling over-blowing by Brötzmann on all three reeds, the Drake/Parker collaborations when Brötzmann drops out (as on the second & third parts of "Never Run But Go," & the enlightening "The Heart & The Bones"), & spectacular contributions from all three as soloists & as part of the group. Posthumously dedicated to Peter Kowald the discs represent the best of modern creative improvisation as the strategies pursued include focusing on building & releasing tension, maneuvering through complex time signatures, & generating magnificent clusters of sound that recall the best of later Coltrane. The short closing number on the second disc, "Half-Hearted Beast" is a rousing chord-based blues-drenched romp that opens the rafters & leaves the crowd screaming for more, even after two hours of nearly unadulterated intensity. Almost certain to appear on many top-ten lists, Never Too Late But Always Too Early is Brötzmann, Drake, & Parker at their best, & it is an important & valuable contribution to each of their discographies.

Recorded live in Montréal in the spring of 2001, this double CD, despite being dedicated to the late Peter Kowald, was actually performed before his death. The dedication is out of affection and respect rather and as something literally recorded for him. That said, Brötzmann, Parker, and Drake reveal in depth here just how they have gelled as a trio. With Parker employing the doussin gouni as well as his bass, and Brötzmann utilizing a taragato and A-clarinet, this is not a skronk session, though there are certainly elements of that, and it certainly is out in its approach. As one would expect, the intensity level is high from the jump as the band begins with the four-part suite "Never Run but Go." Brötzmann uses the clarinet like he does the tenor, blowing not out of the instrument but completely through it, expanding its sonic palette with blurred smattering tonal blurs that do not reflect the instrument's soft, round, and refined tonalities. In fact, his playing on part one, full of ribbons of legato phrases and pulsing intervallic sequences, is reminiscent of Coltrane's soprano playing on the Afro Blue Impressions concerts. Parker matches Brötzmann, coursing a pattern of rhythmic excess that leaves no space unfilled. This isn't about dynamics or tension, it's about intensity and movement, and while for these three it does not run, it certainly does go, through a series of tonal structures that were certainly directed and purposeful. Drake's rhythmic dramatics offer the clues as he returns the signatures from 7/8 and 5/8, moving into overdrive to 11/8 before downshifting again. "Pt. 2" and "Pt. 3" are all Parker and Drake creating a downright funky pop and groove. Parker states the line and Drake fills in with rubato and rim shots to accent the ends of Parker's lines. "Pt. 3" signals Brötzmann's return on the tenor, and Drake kicks it into Afro-Cuban gear as Parker circuitously pizzicatos his way through a Machito/Cachao bassline that gives Brötzmann literally everything he needs to fuse it all together in a solo that is blistering, soulful, and wrapped around three tonal figures that nod to both Drake and Parker, who don't so much follow as extrapolate, adding shifting, broken harmonics to an already splattered sonic canvas.

Disc one closes with the gorgeous "The Heart and the Bones," featuring contrapuntal designations spearheaded by Drake followed by Parker. They round off the edges of opposition and eventually come close to playing against each other, and that's where Brötzmann enters the fray, with as lyrical a statement as you are ever likely to hear him make from the bottom register of his horn -- slow, mournful, spiritual, like Albert Ayler as the improvisation becomes hymn-like for quite a while before erupting into a free for all. The three-part title suite kicks off disc two as a slow, mournful, speculative exercise in bass tonality, with Parker bowing his instrument. Brötzmann moves from the low to middle register in elongated phrases, creating an architectural harmonic complexity and smearing the hell out of one- or two-note phrases. Drake shimmers with a pulse on brushes, keeping the center clean and spare. The pace picks up about six minutes in, but the spareness of the tonal language remains the same. Brötzmann may be blowing out the inside of the horn, but without flurries of notes, as Parker walks it, filling in the extra spaces behind his tonal investigation with pronounced, brief staccato lines. Drake switches to sticks and the band is off and running into the unknown. By the second movement, everything is chaotic and crazy, dark yet celebratory. The audience is screaming for Brötzmann to blow, Parker is in overdrive to add a counterweight to the flight, and Drake pushes it all further, creating a tension that seems irresolvable -- and it isn't until the end of the last movement. The concert ends with a swinging blues, "Half-Hearted Beast," which is literally a barroom romp for improvisers. Never has Brötzmann played in such a guttural, vulgar, and enjoyable manner, nor has Parker walked his bass in such a straightforward way -- though it is far from stride walking. Drake gets to play around all over the edges of the tune, only to bring it back on the turnarounds and carry it out into the night. A fitting end, an amazing ride, and -- dare it be said -- one of the most necessary of the collaborations involving these three men.

Subsequently declared in homage to Peter Kowald, this catches the trio in magnificent form in Montreal. Two long sets have very little that once could call treading water & the potential for Parker & Drake to get funky is realized at several points. A high point in a prolific run of work.

This is a pernicious, pummeling disarray, like all of Brötzmann's albums, and he still makes time for some significant innovations. For a woodwind who began his era of infamy with a music that had no precedents, this particular lineup cavalierly aligns Brötzmann with a rich American tradition of frenetic and dense hard bop (courtesy of Parker and Drake), although that doesn't nearly classify this style of playing-- concrete bop, perhaps, or black-hole-singularity bop. The instruments are still gloriously combusting all over this show, but there's a more melancholy lyricism affixed to them. This is the first Brötzmann album-- hell, first European improv album-- that got stuck in my head hours after it had ended.

From the first ten seconds of the first four-part opus, "Never Run But Go", it's evident that this ain't your father's avant-garde. Brötzmann's shriek of a wraith of a blow bifurcates his clarinet LIKE THE SERPENT'S TONGUE IN EDEN. Parker starts walking up and down, occasionally allowing some tones to break asunder and reinvigorate the clarinetist. Drake is playing the most fervent fills ever conceived, with rolls occurring about every ten seconds. The 45-minute piece is probably one of the most accessible avant-garde jazz moments of the last few years. This is some mad, foaming audacity, but it does have a rhythm (one not recommended for small children or pregnant women).

On "The Heart and the Bones", an initially catastrophic lunacy suddenly goes from Parker sawing his bass in half with the bow into a meditative and elegiac line that sounds like a vacation in Polynesia, except instead of birds in the trees, there are amped-up coffee machines. It's perversely soothing, although I still can't decide if Parker's riff is closer to Reich's Music for 18 Musicians or the Crash Bandicoot soundtrack. Either way, the respite is greatly appreciated. (And I use "respite" cautiously here; Brötzmann is still playing at frequencies that make dogs shatter.) The second disc, while nearly as essential, is a more traditional Brötzmann: less fills, less funk, and more carnage. The titular piece starts with some light brushing and leads into a more "intimate" version of his great band works of the 70s. The final track, "Halfhearted Beast", is unlike anything I've ever heard in free jazz, a blues bounce that seems to intentionally regiment Brötzmann's sax, and I still don't know whether to take it seriously or not.

Brötzmann's style is one of those wondrous achievements that we hope employs digital effects, if only so we can sleep soundly at night knowing no one has that much organic power. He typically pulverizes the horn, blowing straight through it and consciousness. Thus, any two-disc set of his work is a little like going to the Santa Cruz Mystery Spot twice in two hours. Pack your bags.

It's a marathon ride, and from Brötz's opening shrieks on tarogato you know that seatbelts should remain firmly fastened. The trio cycles through most of its moods, registers, and instrumentations throughout the long and rewarding sets: crushing funk, rolling free expressionism, muscular swing, and the occasional dark textural mood. The latter is the rarest commodity for this band, so it's a pleasure to hear the dark melancholy that opens the second set, where Brötz's bass clarinet speaking mournfully to Parker's arco bass. And though this set slowly morphs into a more abstracted rendering of the same territory that opened the first set, Drake shifts frequently into his colorist mode here, a fine reprieve from the Blackwell-on-steroids grooves that tend to dominate (albeit exhilaratingly so). The second set additionally features very good, expressive bass and drum solos. And both discs are filled with the nice, harsh lyricism that distinguishes this band.

Though the two-CD Never Too Late is dedicated to Brotzmann's late collaborator Peter Kowald, it was recorded nearly a year and a half before the bassist's death in 2002. Still, whenever Brotzmann plays with bassist William Parker and drummer Hamid Drake, there is a palpable aura of spirits unleashed, furiously seeking right. At the outset of these disc-long sets, Brotzmann sets a tone that could be called contemplative were it not for the piercing quality of his taragato or the foreboding tone of his alto clarinet; with Parker and Drake's ever-shifting rhythmic weave underfoot, Brotzmann then steadily raises the heat, ultimately switching to his tenor, which plies a sky-shattering cry and an earth-opening growl. Regardless of the timing, the cathartic power of this album makes for a fitting tribute to Kowald.

This free blowing monster of a set very nearly eclipses Machine Gun, Brötzmann's legendary 60s big band LP.